Writing for Dicey Dungeons

Over the last six months, every now and then, I’ve been doing a little bit of writing and story development for Dicey Dungeons. Dicey Dungeons is a videogame from Terry Cavanagh and Marlowe Dobbe and Chipzel and Justo Delgado Baudí, plus a bunch of other people (like me) doing other bits of work around the edges.

This is the first time I’ve written for a full-on videogame! I’ve made my own little text-based games, I’ve written prototypes for clients, I’ve written about games - but this is the first time I’ve done the thing of coming into an existing project and having a look at the bunch of stuff that’s slowly accreting into a videogame, and sitting down and trying to answer questions like “what is this ABOUT” and “who ARE these characters” and “how do the players even KNOW what’s GOING ON” and “how long can this sentence go on before people JUST STOP READING” and “wait WHAT do you mean the game mechanics have changed completely and our earlier cutscenes don’t make sense any more”.

Notes from an early brainstorming session with Terry, Niamh and Marlowe, about what the theme of the game should be

It turns out: it’s pretty great!

I've always loved writing with constraints, and videogame writing really is, notoriously so, a matter of dealing with a hundred different constraints at once: the game design is often finalised, or dramatically changed, without you; lines will have arbitrary length limits which may or may not also suddenly change; character motivations are unclear but have to be (a) coherent and (b) justify three different seemingly opposed actions, for reasons of Well, The Plot Says So; maybe you’ll even discover partway through that certain punctuation marks are banned because they’ll confuse the computer…

Dicey Dungeons itself, in terms of gameplay, is basically Exercises in Style for game design. There are six different characters competing on a fictional game show, and each of these character has six different "episodes" with significantly different rules. The game really digs into all the different ways that the fundamental ruleset underlying the game can be expressed and tweaked and twisted.

So the game world that sits outside these episodes had to be something that supported all these different styles of gameplay, and made sense of them co-existing, and which also could carry on through 36 different episodes without becoming boring or nonsensical or exasperating. The underlying game show concept was already there when I got involved - but almost everything else was up for grabs.

I don’t think I could talk about the whole process of writing the game without going on for way longer than anyone would want to read - so I thought it might be interesting to instead look at how I ended up approaching one particular question:

Who are all these enemies you’re fighting anyway?

There are seventy or so different enemy creatures that you fight against in Dicey Dungeons: a cheerful jester who co-hosts the game show, figures from Irish mythology, a tiny terrified cactus, an imperious bee.

When I got involved most of these characters existed already, in the form of Marlowe’s illustrations and animations, and Terry’s decisions about what equipment they have and how they fight. So the questions to resolve were:

Why are they in these Dungeons anyway?

Do they say anything? If so, when?

And… what?

We decided they were a mix of enthusiastic game show minions who’d signed up for their jobs; people who blundered into the Dungeons by accident and got stuck there; and previous competitors on the game show who lost and who are now stuck in the Dungeons for ever. This last one turned out to be a super useful decision in terms of providing a threat to hold over the heads of our six dice heroes: if they didn’t make it out, they’d be trapped as minions for eternity.

To establish this, though, the enemies needed to be able to talk. Not all the time, of course, because for a start we just didn’t want there to be that much writing for people to read through (and for the translators to translate - it really helps keep the word count down when you’re conscious that for every sentence you write, a dozen people will be translating it!).

We settled on each enemy having a line or two (as the game developed, this grew to three or four) in stock, and perhaps they’d say one of those lines if you beat them - just occasionally. Most enemies would be silent most of the time, but maybe you’d hear from one of them every 10-15 minutes, and if you played for long enough maybe you’d get a bit of a sense of who they were.

So what do they say?

So the enemies have maybe three or four lines each, total, which isn’t much. But those lines needed to get across a personality, and to fit with their animation and design, and to be meaningfully distinct from all the other characters.

It turns out it's pretty challenging to think of seventy-odd different types of response that a fictional character might have to being beaten in a fight! I started classifying the characters into different categories, to make sure that we ended up with a good variety: some Friendly, some Supportive, some Competitive, Wistful, Snooty, Annoyed, Bored, Weird, Grandiose, Threatening.

And then I thought about what might be possible with the tiny space we had for writing for each one.

I thought about Twitter and about kinda meandery books like Sei Shōnagon’s The Pillow Book or Robert Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy, where the writers say things extremely confidently and don’t really worry that readers might not have the context to understand what they’re saying. And how that certainty in itself implies something about the larger context.

I thought about picaresques and about journeys and about books and movies and games like Labyrinth, The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, The Phantom Tollbooth, the games at my primary school like Granny’s Garden that were getting old even back then, the grumpy frog with its riddles in Candy Box, basically anything where you encounter a character and leave them behind but they still manage to make an impression, to be one of the things that sticks in your head.

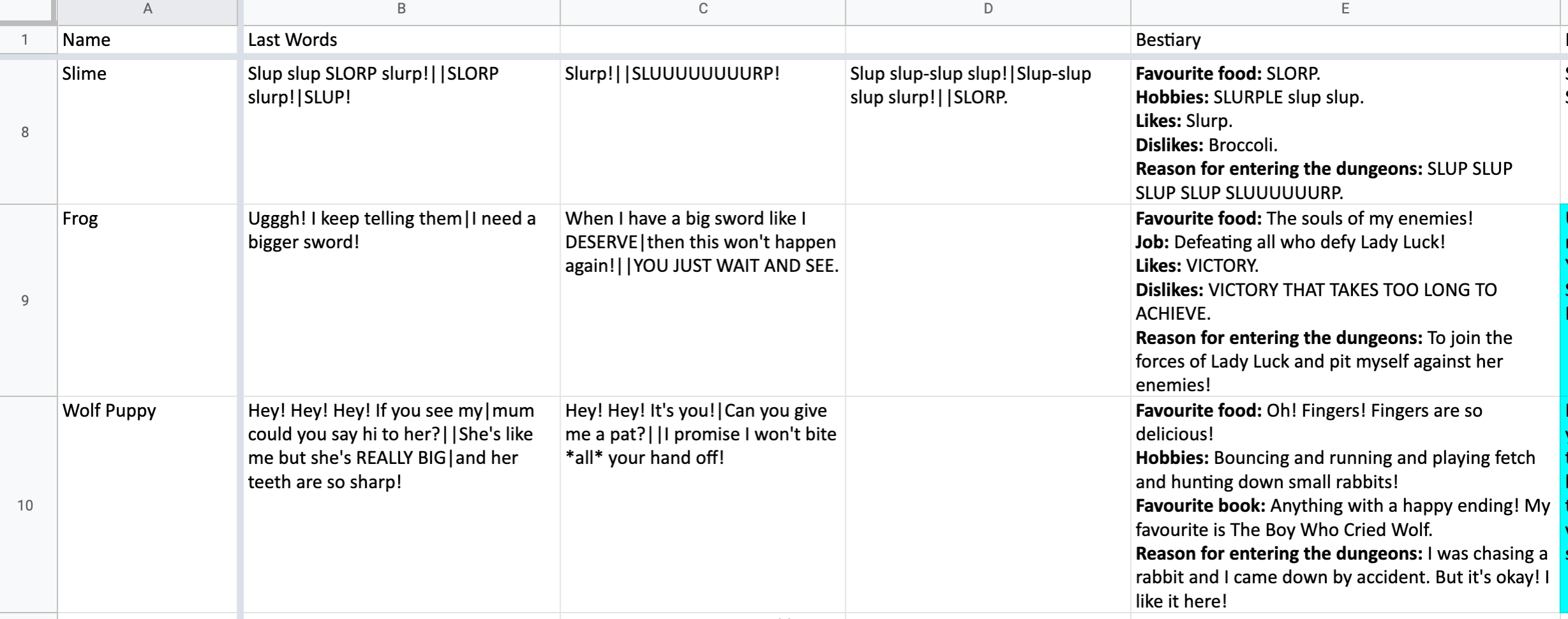

Which is, sure, a fairly grandiose-sounding set of things to think about for writing that ended up looking like this:

If each enemy has three or four lines - and those lines might appear with five-hour gaps of playtime between them! - then the most important thing about them was that they be distinctive and consistent. There wasn’t space for much subtlety, or for a gradual evolution of the characters! I basically picked one joke or one dominant personality trait for each character, and went with three or four different variations: four schoolyard chants, four different sneers, four different excited greetings. So the Kraken is always sleepy and furious. The Wolf Puppy is enthusiastic, and really likes to eat hands. The Handyman is also enthusiastic, and has six hands (it seems like maybe he could come to some arrangement with the Wolf Puppy, but that’s - well, outside the scope of the game).

Towards the end of the writing process, Philippa Warr came in and spent a week editing: correcting spellings, having much more contemporary opinions than I do about “for ever” versus “forever”, writing extra jokes, pointing out when things sounded inadvertently ruder than I’d meant them to. This was really great - obviously having a good editor is amazing anyway but it was particularly vital in this case given that there was so little time to revise the text; often it had to go off to translators within a few days of being written, and after the translators had it, that was it.

And so here I am, four days from launch, with nothing to do except sit around and occasionally adjust the timings of some of the lines! It’s a bit nerve-wracking! But also: I’m really very excited for everyone to meet Baby Squid.